Kokuta Suda

1906 to 1990

JApon

Biography

Like so many artists Kokuta Suda was passionate about art from a very early age. His dream of becoming a successful artist was not shared by his father who did not support Suda’s choice of carrier. However during his teen years Suda suffered some issues with his kidneys which left him bed ridden for many months giving him time to pursue his passion. His illness was life threatening and this experience haunted him for the rest of his life leaving Suda physically weak and insecure.

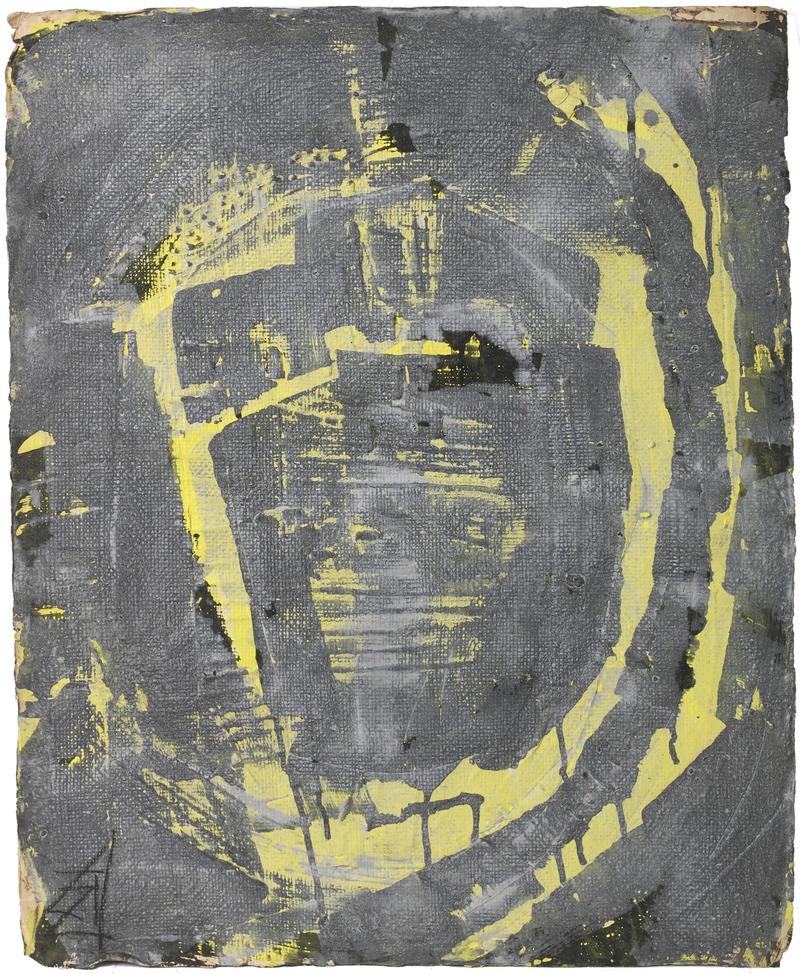

Despite these adversities his will was strong and Suda dedicated himself to becoming an artist and applied to enter the Fine Art School Tokyo. He failed four times! This could be seen as a positive outcome as he could now work freely without the dogma of an old fashioned institution. He began to paint pieces of meat and became obsessed with the subject, painting it again and again over several years in an attempting to capture the essence of the flesh within his canvas. His search is said to be one for the quintessence of art and the goal was to impart emotion and soul into his work. He admired Van Gogh, Picasso and Modigliani but refused to copy any other artist and staunchly followed his own path.

At this time (Suda’s mid twenties) Japan was also going through a period of major modernisation. This process led by foreign influence introduced many new building materials to Japan, one of which was asphalt. Suda was fascinated by the new road surface and even tried to steal some, leading to an arrest and several hours at the local police station. The thick sticky texture inspired him and can often be seen in his work.

At the age of 27, he was visited by Manjiro Terauchi (1890-1964), an important and influential artist of the Western style. Terauchi had seen one of Kokuta's paintings of meat in a collective exhibition, and astonished by the power of the lines and texture, he convinced Suda to move away from this obsession and to paint other subjects. This meeting changed his life.

In 1935, Kokuta gained some success showing works at two major exhibitions, however, his close friend and colleague Sadakatsu Nagafuchi was not so lucky and was not chosen. This rejection led Nagafuchi to commit suicide and left Kokuta with a great sense of guilt as he believed it was partly his fault. This tragic episode had an enormous impact on him, taking him close to a nervous breakdown. It was at this difficult time that he met Soetsu Mineo (1860-1954), the chief abbot of Heirin-ji temple, a Zen Buddhist temple.

After this initial meeting, he visited the temple regularly and they had long and deep conversations about spirituality. Without really understand it, he discovered in Zen Buddhism a way to find the light. He was 29 years old and his mind began to open. Kokuta Suda always had the ability to express his negative experiences through his art and his new found interest in Zen Buddhism allowed him to evolve and to go to the next stage.

Soon after in his early thirties Suda began to win prizes and had a small following of collectors and also gained a patron who offered him a small stipend along with a small studio. While basic this support and freedom allowed him to develop his own personal style and to get closer to his goal of paintings which could enlighten people as he struggled to impart his soul directly on to the canvas in style different from any other artist.

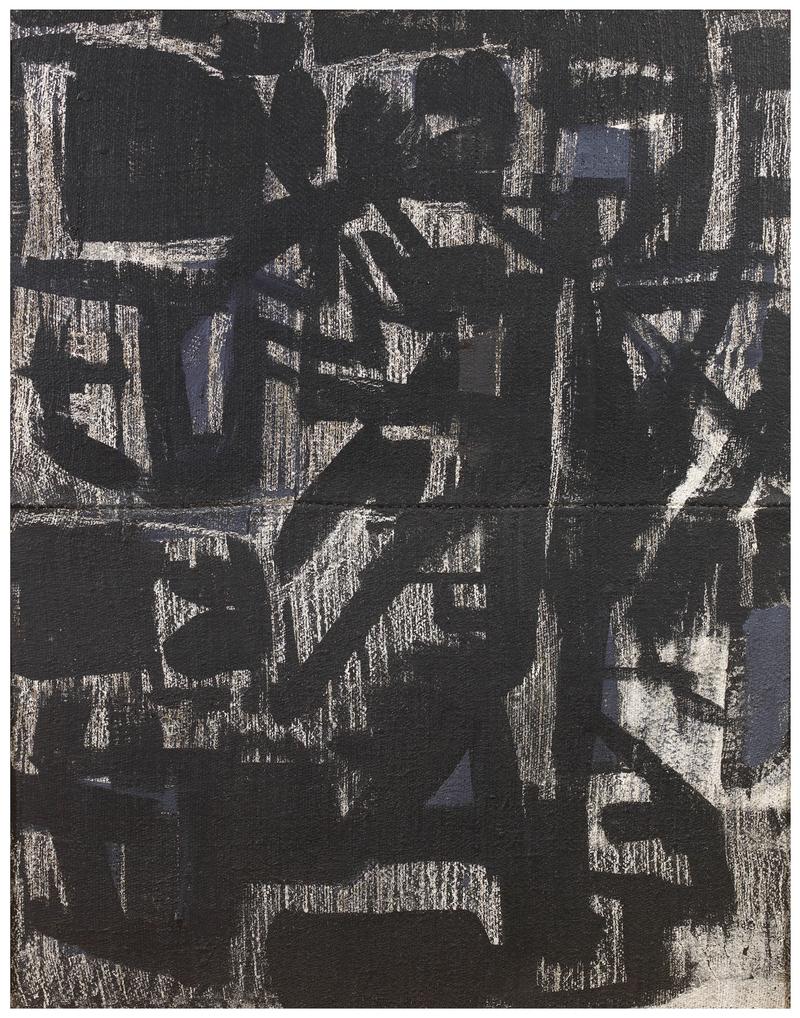

Having met Soetsu, he began a serious study of the philosophy of Zen Buddhism which inspired Suda to paint numerous Buddhist images. The more he studied Buddhism, the stronger his interest became, leading him to visit temples in the Kansai region often. Eventually a priest offered him a mud-walled warehouse in Kannon-ji temple Nara and Suda used this as a studio and basic accommodation. He stayed for two years, spending his days painting the many important Buddhist artefacts held in the city. He was deeply attracted by the power of these sculptures and tried to express their vitality through his work.

During the Second World War Suda was forced to work in a factory for almost two years making it impossible to focus on his art. During this period, he composed poems as a substitute and continued to visit all the great temples in Nara, becoming more and more insightful. The war finally ended and Suda was free to paint again. Unfortunately it was around this time that his sponsor died leaving Suda without an income. Fortunately for him he was invited to become a part-time teacher at an elementary school which would provide him with enough money to live. He was amazed by the freedom of expression and creativity of the children. When he was teaching to older students, he pushed them to develop their own style, to be different from the others, insisting on the importance of individuality.

He also decided to join other artists in discussion groups in an effort to expand his horizons and in 1949, during an exciting and controversial art circle talk, the famous abstract painter, Saburo Hasegawa (1906-1957), suggested that Kokuta should study Asian philosophy and read the teachings of the monk Dogen (1200-1253), author of Shobogenzo (the essence of enlightenment). Apparently he found it to be the most difficult philosophical book he had ever read but was desperate to fully understand the ideas of the priest and so he read it repeatedly. By studying this book, it allowed him to look deeper into himself and to have a better understanding of the abstract qualities of Zen. A quality which he then tried impart into his own work which now shifted from representational to abstract inspiring him to express his inner thoughts into a concrete form. He was excited by this new way of expression and finally began to enjoy his life as an artist. The Shobogenzo which he studied for the rest of his life, served as a theoretical support for his abstract paintings.

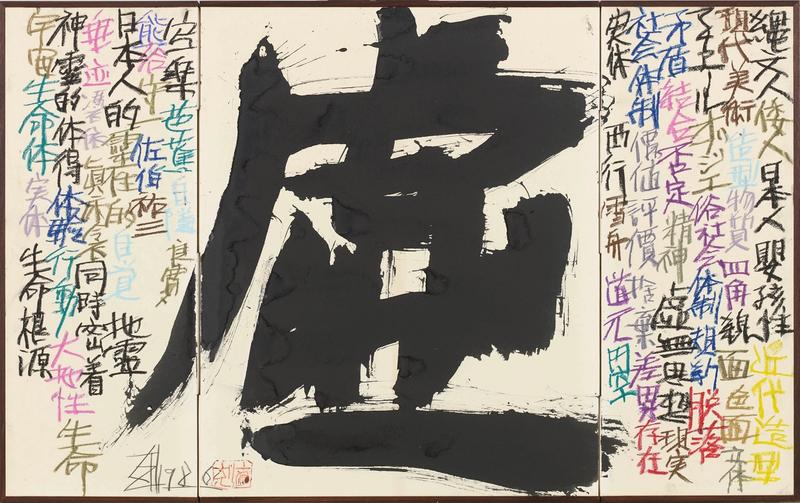

In 1950, Kokuta wrote his first essay on art which focused on calligraphy. This was published in Shonobi (Beauty of Calligraphy) sharing some important ideas with its main contributor and close friend of Franz Cline, Morita Shiryu (1912-1998), the famous avant-garde

calligrapher. By writing down his ideas, he steadily established his theory of abstract art. He thought that lines were a kind of global language and that they were effectively a self-portrait of the calligraphers themselves. His obsession for the quality of the line, his talent as a painter and his strong spirituality soon brought him recognition as an outstanding calligrapher.

In 1955, he was invited by his friend and fellow artist Yoshihara Jiro to join the new avant-garde group Gutai but he declined preferring to stay independent in his creative process.

His status as an artist in Japan rose and he was invited to show his work at overseas exhibitions. He represented Japan, at the 4th Sao Paulo Biennale in 1957, followed by the 11th Plemio Resonne International Art Exhibition of Italy and Houston USA in 1959 followed in 1961 by Carnegie, Pittsburg USA and Berlin, West Germany.

Suda focused on an abstract style and calligraphy for a further 20 years. He was never afraid to change his approach and continued to use the painful times of his youth as a powerful tool. When he came back to figurative representation in the 1970’s/80’s, a trace of abstraction remained on his canvas and he enjoyed to mix both styles. He also improved his knowledge and technique of calligraphy at this time and began using a thick young bamboo brush to express philosophical words with dynamic lines full of vitality.

In 1971, he was asked to illustrate a newspaper series entitled Going along the road which was written by the acclaimed author Ryotaro Shiba (1923-1996). The collaboration between the two was a powerful one and the series with its brilliant text describing life in Japan during the Showa Period accompanied by the inspiring illustrations was a huge success and formed the begging of a twenty year long relationship where the pair travelled extensively, first across Japan and then on to Korea, Mongolia, and Europe. In total Suda produced over 900 illustrations for the series, bringing him national recognition and further success.

Suda received a prize of honour from his home town of Fukiage 1976 he considered it as the biggest honour possible.

In the last year of his life, he said that he finally felt he had mastered his chosen mediums of oil painting as well as ink and 1989 he produced more than 500 works, putting all his final energy into this over.

He spent his last days drawing from his hospital bed. Before his death Kokuta Suda donated approximately 3000 works to several museums in Japan. He died on July, 14th 1990 after a life of single-minded dedication to the practice of art and the spiritual qualities within it.